|

| (A Tom Lovell portrait of Walt Reed) |

|

| (Murray Tinkelman, Walt and Roger Reed at Illustration House) |

|

| (Walt receiving an award for his work in illustration.) |

This week the art world lost of the great proponents for the field of illustration with the passing of Walt Reed. With his books on the history of illustration in America, and his gallery Illustration House, Walt raised the status of the illustrator to that of fine artist. Besides being a writer, and an instructor at the Famous Illustrators School, he was also an exceptional artist in his own right- though he was slow to accept this simply because of his knowledge of so many greats he worked with. It was my pleasure to meet Walt a number of times over the years, and he always graciously shared his time and knowledge as he allowed me to browse through stacks of original illustrations and the tear sheet files as his gallery; and so many many other had the same experience which helped them reach a new level of development in their work. Our condolences to his son Roger and all of his family and many friends; Walt is a man we will all miss.

The following is a reprint of an interview with Walt Reed that appeared in the magazine North Light in 1978.

Pictures have fascinated me for as long as I can remember. Not only is it a challenge making my own pictures, but the appreciation and study of the work of other artists have been a source of continuous pleasure and interest. While my appreciation includes approaches as diverse as those of Picasso, Wyeth, George Herriman’s :Krazy Kat”, Rembrandt, African masks, Japanes prints and calligraphy, I admit to a special interest and love for American Illustration.

While I was still an art student at Pratt Institute in Brooklyn, one of my teachers, Nicholas Riley first introduced me to the wonderful world of Howard Pyle, founder of the Golden Age of American Illustration. As an art student, the magnificence of Pyle’s drawings and compositions, as well as his concepts, impressed me tremendously. When not attending classes, I would spend my free time browsing in second-hand book stores where one could still readily find bound volumes of back issues of the old Harper’s Monthly, Scribner’s, McClures and Century magazines which contained the work of Pyle, Edwin Austin Abbey and many other great illustrators beginning back in the 1880’s and continuing on through the turn of the century. I gradually began to acquire a large number of printed examples of their work which eventually threatened to crowd me out of my small YMCA room. Of course, at the same time, I was very much aware of the work being done by contemporary illustrators, then led by men like Dean Cornwell, Norman Rockwell, John LaGatta, Harvey Dunn , and Pruett Carter. As I studied their work, I began to recognize their styles and was able to identify virtually all of the illustrators who were or had been practitioners of any importance. I carefully clipped tear sheets of their work and filed them away alphabetically as part of my general art reference file. As time went by, this part of my file took over in volume and affection.

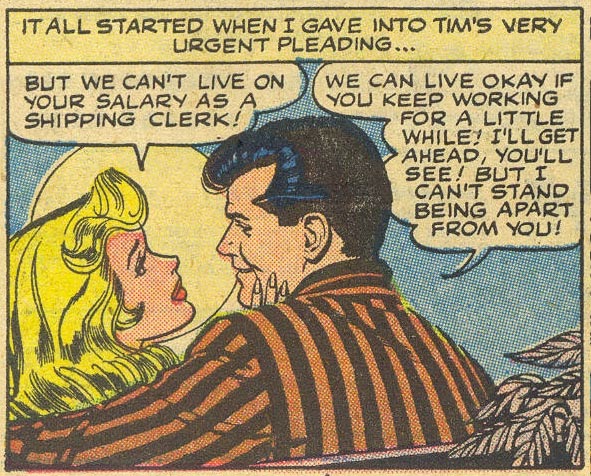

After art school, Pratt Institute and the New York-Phoenix School of Design, came marriage to an attractive young assistant to the picture editor of This Week magazaine. There was an interlude of trying to get established as an illustrator and the frustration- and appreciation- of being supported mostly by my new wife. Then an opportunity came to go abroad as an overseas staff member for C.A.R.E. That agency, formed in the aftermath of World War II, was engaged in the hire relief effort in most of the countries of Europe and later into underdeveloped areas in all parts of the world. When I was offered the job opening Czechoslovakia, seeing a new part of the world was too good an opportunity to pass by, so in 1948 my wife and I arrived in Prague and thereafter spent the next four years successively in Finland, the Middle East, (based in Lebanon), Greece and Yugoslavia.

During our stay in Europe, there was a lot of hard work in supervising distribution of relief package and commodities. There was also an opportunity to really absorb the feel of the countries, since we stayed in each one a relatively long period of time. I was fortunate, as well, to be able to record our travels through sketches and paintings.

|

| (An illustration for a C.A.R.E, brochure showing the distribution of self-help supplies in the Middle East.) |

In 1952 I returned to the New York home off of C.A.R.E. to become the Art Director for the parent organization. I remained for three years and then left to free lance in the book publishing field. In 1957 I joined the instruction staff of the Famous Artists School. Teaching others was as much an aid to improving my own skills as it was in helping others, and my free lance work became much stronger.

|

| (An Arabic resort area on the Mediterranean near Beirut, Lebanon. The small cottages are built on stilts to catch cooling breezes and to provide some privacy.) |

My affiliation with the Famous Artist School also provided a marvelous opportunity to know and work with a large number of professionals including the famous guiding faculty. It was a privilege to meet artist like the late Albert Dorne, founder of the School, Harold Von Schmidt, Normal Rockwell, Steven Dohanos, Austin Briggs, Peter HelcK and Al Parker whose work I had followed and greatly admired.

The faculty member who influenced me most strongly was Harold Von Schmidt and he was kind enough to advise me about some of my professional assignments. As I learned more about his colorful career, it occurred to me that an interesting book should be written about him and his pictures.

Before long, the idea of doing a book about “Von’s” illustrations began to take on a larger dimension, and I wondered if it would be possible to do a book on the whole history of that inspirational period of illustration. I realized that I was in a particularly advantageous position to undertake such a project, since I not only had much of the past material at hand but also had contact with so many of the living illustrators who were either affiliated with the school or who lived in or near the town of Wesport. Al Dorne was very enthusiastic about the idea, and it was he who got the project off the ground by introducing me to Jean Koefoed of Reinhold Publishing Company.

With the contract signed, the next five years were spent in the monumental job of obtaining and selecting the best examples of work out of a particular artist’s entire career, tracking down the artists or relatives of deceased artist, obtaining permissions and then layout out the whole book in some order. The project began as a labor of love and remained so, even though it meant eliminating any other activities beyond my teaching at the school, thus sidetracking my own career in illustration.

Once that book was completed, there was still the story on Harold Von Schmidt, Harold Von Schmidt Draws and Paints The Old West, to be done and that became my next project, just completed.

When Bill Fletcher invited me to join the North Light staff, I was delighted to have the opportunity to use this combination of interest in art and writing even more fully. I look forward to the prospect of working with editor Howard Munce and to help in the development of books which will impart their instruction and inspiration. We hope that you will enjoy the results.

( Walt Reed 1978 )