When I was about twelve years old Mad Magazine started reprinting in paperback form in black and white some of their comic book parodies. Many were by Jack Davis who was the first artist I tried to emulate, but my real Mad idol was Wally Wood with his slick style and very sexy females. He had illustrated Superdooperman, Batboy and Reuben, Flesh Garden and many others, but my favorite was Teddy and the Pirates, with the lascivious Dragging Lady.

|

| (Wally Wood's parody with the wondrous Dragging Lady.) |

The Terry and the Pirates strip I was familiar with was drawn by George Wunder, and all the characters had these oversized and distorted eyes, and the look of the strip was pretty gloomy. And it was about guys in the army. My youthful sensibilities found little to attract me. There was certainly none of the magic that Wally Wood hinted at in the Mad parody. It wasn’t until I was in my late thirties that I finally that I finally saw the Nostalgia Press reissues of Caniff’s original strip. Needless to say, I was hooked.

|

| (George Wunder's version of the strip.) |

And so Caniff’s Terry and the Pirates was one of my biggest influences. Along with Prince Valiant, the Phantom, Manrake the Magician, Flash Gordon and Dick Tracy, it was arguably one of the greatest adventure strips ever done. It was drawn in that brief time period when the adventure strip truly blossomed, with a host of talented draftsmen presenting a daily dose of action and excitement. The creators were household names and made fabulous salaries. But with the advent of television and the competion from comic books, by the early 70’s there was only remnants of the medium left.

When I was sharing studio space with Howard Chaykin, I borrowed his Flying Buttress volumes and started reading through the entire Terry and the Pirates strip from its inception in 1934 till Caniff left it in 1946 to start work on Steve Canyon. The experience was an education unlike anything I had come across in comics. I was enthralled…watching Caniff’s early cartoony drawings quickly transform into an elegant, realistic strip. The busy linework of the early days was discarded for a dynamic use of black that solidified each and every frame. What had started out as a “cartoon” strip, became a daily presentation of amazing illustrations.

|

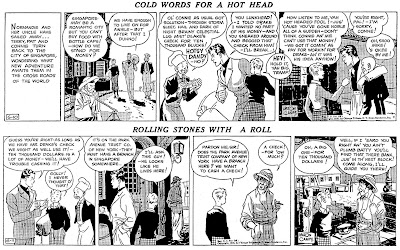

| (You can compare these strips with later ones to see how much Caniff's work advanced in a very short period of time from cartoony to very realistic.) |

|

| (Caniff in his studio with an assistant and a model.Lucky guy...) |

Of course, Milt was aided at the time by his studio mate, Noel Sickles, who helped him a good bit with backgrounds and developing his style and his drawing. Sickles was drawing his own strip, Scorchy Smith (which also travelled a quick road from cartoony to illustrative under his hand). He was the better draftsman, and Caniff was the better storyteller. His influence on Caniff’s drawing was immediate and dramatic. Sickles eventually left comic strips to work as an illustrator, eventually be elected into their Hall of Fame.

|

| (Noel Sickles at the board.) |

|

| (One of my favorite Sickles' illustrations- a tour de force of linear simplicity. Another stunning example below.) |

Young Terry is the ward of Pat Ryan and the two of them are roving about the China seas in search of fortune and adventure. While their Chinese sidekick Connie is drawn as a racial stereotype, he is always portrayed as the smart, loyal, and brave companion. He is one of a trio, and not simply a figure of ridicule. And then there were the women in the strip. They all seemed to form an attraction to Pat; Normandie Drake (think Claudette Colbert) is his first big love, but when Burma (Marlene Dietrich) enters the scene, the heat is raised to another level. And in the midst of all this there is the Dragon Lady- and you’re never quite certain whose side she is actually on, but you couldn’t help but see her as a sympathetic character. To paraphrase the Grateful Dead, what a long, strange strip it was!

|

| (Two examples of Sickles' Scorchy Smith strip.) |

|

| (The Dragon Lady in and out of costume, and below the vivacious Burna.) |

The stories that Caniff brought to Terry were where you saw his real strength. While they were certainly influenced by the movies of the era (the late 30’s), the characters and plots could always hold there own with their cinematic partners. Check out The General Died at Dawn and China Seas for two that certainly influenced Terry.There were also elements of Sax Rohmer, Dickens, H. Ryder Haggard and other adventure novelists. The strip was a true romance in the literary sense: a fictional narrative of chivalric heroes. World War II changed all that. Terry morphed from a soldier of fortune, to a U.S. soldier, and the strip, or more to the point Caniff, was never the same. What had been a grand adventure strip now was becoming an piece of army recruiting propaganda. At the time, that wasn’t such a bad thing. The naiveté and innocence that had fascinated the American public was now replaced with a patriotic pragmatism.

If you look at films of the 30’s and 40’s you can see what starts to happen in Terry even before the war. When the Great Depression staggered the economy, people wanted to escape with the exotic, the luxuriant and a world beyond their reach. When in the forties the war brought prosperity back, people started tamping down their fantasies. They were attracted to a more mundane and stable life style and wanted to see more realism in stories. The interest in China was no longer as an exotic locale, but as a strategic military ally. In keeping with this, the artwork in Terry developed a rougher, grittier, more realistic approach.

|

| (A couple of Terry Sundays from WWII.) |

During the war, Caniff was actively involved in working with the American military on a number of projects. Visitors to his studio in those days were asked to sign the guess book by an armed guard as often the material they would see Caniff working on might be classified. And Caniff welcomed and warmed to this task, so much so that after the war, he bowed out of Terry. He had never owned the strip but had been hired by King Features Syndicate. The strip he developed, and retained creative rights to, was Steve Canyon. The hero was an officer in the U.S. Air Force and the tone of the material clearly reflected Caniff’s own patriotic fervor. The stories were set with the Air Force backdrop, and while Steve might venture off base, you always were aware of his military allegiance. As a youngster, both the rough inking style and the military focus simply did not attract me.

|

| ( Steven Canyon enters the scene for the first time.) |

The art in Steve Canyon might have had a better draftsmanship,there were any number of unique characters peopling the frames, there were fascinating compositions and even more literary stories, buy the strip simply didn’t have the elegance and innocence and romance of Terry and the Pirates. The writer Graham Greene received critical acclaim for his “serious” novels:The Power and the Glory, The End of the Affair, The Quiet American,etc., but he blithely referred to The Third Man, Odd Man Out, and The Fallen Idol as his “entertainments.” But in the business of entertainment, The Third Man is certainly the Graham Greene story that continues to have a serious impact even today. The motto I learned early working in Hollywood was, “Never let reality get in the way of entertainment.”

When I started reading Caniff’s Terry and the Pirates I was a mature…er…at least I was no longer a kid. But there was still a magic in the drawing and in the story that captured me immediately. Like the films of Alfred Hitchcock, the appeal was for a very wide audience and for a very long time.