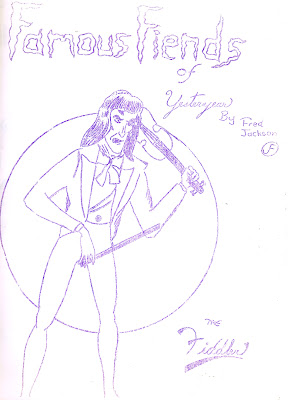

(The cover of Masquerader #1, drawn by Paul Seydor.)

At the San Diego Comiccon this Saturday night there will be a celebration of the 50 Year Fandom Anniversary. While I won't be there in person, I will be there in spirit. Comic fandom was a major part of my life when I was a teenager.

When I was a freshman in high school I put together a planned issue of a fanzine, which I called

Masquerader (hey,

Alter-Ego was taken). It was about 18 pages of material: a couple of ads for comics for sale, an article comparing the Justice League and Society, an article on Sax Rohmer's Fu Manchu books, and my own comic strip, Dr. Destiny. I was so green that I everything I drew was in ink on paper, and the text was typewritten with the drawings pasted on. Very pretty, but there was no that I could print it. On my next attempt, I used the standard spirit duplicator method, drawing and typing everything on stencils. With this process there were limited print runs; after about 200 copies, the pages started to fade out rapidly. And there were frequent accidents with the originals; if they weren't properly clamped into place they would often wrinkle, ruining the page.

But this mock up issue, with Fred Jackson contributing a number of pages, I sent that around to probably Ronn Foss, Jerry Bails and two or three others asking for suggestions and criticism. Everyone was always very helpful, but Ronn and Jerry were certainly my mentors in the field. Their input into what I needed to do to take my fanzine beyond the "crudzine" classification was essential. And of course, the unsung heroes behind all this were my parents who always gave me their support; my dad give me access to the duplicator machine (and paper supply) at the school where he worked as head custodian.

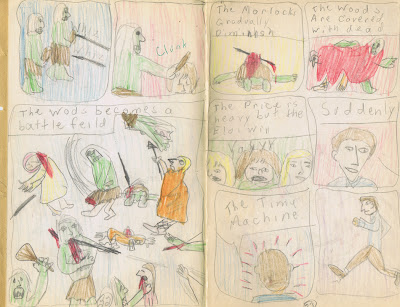

(One of Fred Jackson's illustrations for the first issue.)

The first issue of

Masquerader that was published featured a Hawkman drawing by Paul Seydor on the cover, my rehash and review of one of the JSA issues, my take on the new Marvel heroes, Dick West's article on the New Age of Comics, a piece on the Shadow by Fred Jackson, and Mike Touhey's review of The Hangman. There were several pinups, and two strips: The Blue Bolt (by Fred and Larry Charet with my drawings ) and the Cowl (with my writing and drawn by Ronn Foss.) The strengths of the issue were some really beautiful drawings by Paul, Fred, Ronn and Biljo White. One of my innovations was "justified margins" with the type.When I would type out the articles, I would add a series of "bullets" at the end of each line; when I did the final typing on the master I would add a space for every bullet, so both the left and right edges of the columns looked like a professional magazine. The biggest weakness was that too much of the art was my own crude scribblings. But as a first attempt it wasn't bad.

(This was Biljo's White's drawing for the ad section of the zine.)

With the second issue there were two major problems. The first was that I decided to use black masters instead of the traditional purple. Unfortunately, the "black" reproduced as a light medium grey, and while the purple masters would usually last 2-300 copies, the black dittos were starting to die after the first hundred pages. The second problem was that I wound up doing most of the artwork. I was in a hurry to produce another issue, and the really good artists were booked up for months in advance. The overall effect was that the issue was a step back from the first.

(This and below are two of Ronn Foss's stunning Hawkman drawings.)

The articles were solid: Howard Keltner's "High Flying Hawkman", "Meet Doc Solar" by Gregg Way, Margaret Gemignani's piece on Hourman, Steve Perrin's piece on the Jaguar, my own on Mandrake, Rick West's excellent article on "The Birth of the JSA." Ronn Foss did two beautiful illustrations of Hawkman and one of Captain America for the letter's page, and Grass Green had a great cartoon. Unfortunately, after that there was a whole lot of my doodles, including a really abysmal cover drawing of the Comet, that just proved I had a LOT to learn.

So issue three was bound to be an improvement. In retrospect, I am amazed that I was trying to produce the issues on a bi-monthly schedule. But what really amazes me was how much I apparently improved in two months; while I did far fewer drawings in this issue, they were all remarkably stronger. The only articles were one on Fighting American written by Mike Touhey that I did the art for and a short piece by Foss (using the pseudonym Scott Russell) on defining amateur zines. There were two strips. The first was an Action Ace and Thrillboy story by Grass Green that was the highlight of the issue. The other was Astro, written by Phil Leibfred and drawn by yours truly; whatever else there was to say about it, I believe it was the first "color" strip produced for a fanzine. My cover was well designed and not badly drawn, but again the best art was the spot illustrations by Ronn (Newsboy Legion and the Guardian) and Grass (several ACG heroes). And "Quotes from the Readers" did feature letters from both Gardner Fox and Joe Kubert.

(This strip by Biljo was actually a continuation of a strip started, and continued, in

another fanzine. I'm not sure how often that was done in early fandom.)

The fourth issue was probably the best of the ditto issues. Once again, Hawkman was featured on the cover, drawn by myself. Ed Lehmann did a knockout article on Simon and Kirby called "The Donnybrook Boys", with several illustrations by Ronn. Mike Touhey did a piece on the Shield, illustrated by Grass, and Howard Keltner contributed "The Story of Mr. Justice", with drawings by Biljo White. "Captain 3-D was written by Margaret Gemignani with one of my drawings. My personal favorite was Rick West's piece about Sax Rohmer's Fu Manchu, "Lord of the Si Fan", again with my artwork. Ronn also had a sweet little illo of the Spectre. There was also the knockout strip Astro Ace- the 8th Astronaut, by Biljo White- which was quite stunning. All in all, I was really proud of that issue.

What stands out about issue five was the amazing technical feat of having three different artists all draw their favorite character on the cover: Biljo White did Batman, Ronn did Hawkman, and Grass did Fighting American. What this entailed was sending the dittomaster to each artist in turn, have them do their character, and then send the master on the next artist, and finally to me for printing. You don't think I was nervous when I finally fitted that sucker onto the spirit duplicator machine. One wrinkle and my life was over!

(In the days when you could actually depend on the mails not to lose things

this cover had to be sent to three artists and then myself. )

"Stan Lee, the Man Behind the Comics," was the lead off, which I wrote and Ronn profusely illustrated. Ed Lahman did a piece about five of his favorite characters which Grass did the drawings for."Radar- International Policeman" was written by Ray Miller and featured the first artwork by Alan Weiss in Mask. Margaret Gemignani wrote about Bulletman and Bulletgirl, with my illustrations. It also featured a foldout pinup of my drawing of Viking Prince. We weren't always brilliant, but we were innovative.

Which is why I chose to print the sixth issue of Masquerader on a photo-offset press. Producing the pages for the press was much more difficult than working on the ditto masters. With every page I had to cut out whatever I typed and carefully place it and glue it into place on the master sheet. Same thing with any artwork. Then any excess rubber cement had to be cleaned off. It was a time consuming process.

(More of Ronn Foss's artwork.)

Masquerader #6 was one the very first comicbook fanzine printed this way;

Alter Ego #5, which Ronn Foss produced, came out just before this issue. I do remember was that the issue was ready to print long before I had the money to pay for the printing, which was about $250. At 50 cents a copy that meant I had to sell 500 copies to break even, and that was before postage. With the limited size of comic fandom that wasn't going to happen. Fortunately, my parents who supported me in all this weird comicbook stuff, stepped in and told me to invest some of my own money and get the issue printed.

Then I had to wait about five weeks for the printers. Patience was not one of my virtues. The spirit duplicator had always been so instantaneous. You finished the masters, ran over to dad's school on a weekend, and printed an issue. I was getting pretty antsy....but eventually I got the call that my issue was ready. Well, not quite. They did advise me to wait two to three days for the ink to dry properly before I started to assemble the issue. I couldn't afford to pay the additional fee for machine assemblage and trim.

(An early drawing by Alan Weiss, who developed into a magnificent talent.)

There were eight to ten boxes of ledger size sheets. I would lay out stacks of the seven sheets (each with four pages printed on each one) and the cover sheet (on a different blue stock). I conned my younger sister Sue, who was about six at the time into helping me put the pages in the right order. Since I didn't have an oversize stapler I would open the one I had and put two staples face down into the center of the pages with a heavy piece of cardboard under them. Then I would pull pages up and manually fold down the upright staples. It really was a work of love. Then the issues had to be addressed, a stamp stuck on them, and they were sent out.

You can view the issue on my flickr site, so I won't take a lot of time describing it. The highlights for me were Ronn's beautiful pages of the Cowl, the two full page illustrations Dick Memorich did as a tribute to Jerry Robinson's Batman, and the Viking Prince splash by Kubert that was reprinted for the article about Joe. My correspondents were very generous with their praise of the issue, but I'm not sure I ever saw or can remember reading any "reviews" in what there was of the fan press at the time. But after a year and half of publishing, I was pretty burned out. My fanzine days were pretty much at an end.

In later years I would come out with two oneshot zines:

Savage Princess and

Beyond Infinity. But both of them were more self-published comics than zines. The first was done on the dittograph and my pastiche to Kubert's Tor and Frazetta's Thunda with a dash of Wood and Williamson thrown in. I doubt if I printed more than a hundred copies. Beyond Infinity was another photo-offset book, with three E.C. type stories in it. Sales and distribution were very limited. Both of them were attempts to establish myself as an artist; I had little or no interest anymore in establishing myself as a writer or editor.

The great highlight that I talked about in Bill Schelly's book on fanzines was the amount of mail I received. A lot of it was envelopes with nickels, dimes, and quarters to pay for an issue of

Masquerader, and a lot of it was correspondence with so many wonderful and interesting people who didn't seem to mind writing to this nerdy teenager.

One of the most important things I learned from working on my fanzines, was the importance of drawing for reproduction. It didn't matter how beautiful a drawing was in its initial stage, the real test was when it was copied and printed in whatever medium you were using. Working on the dittomasters required a very simply linear style. You could be a bit more clever with the line for the photo-offset jobs, but you quickly learned that those delicate fine lines that look so pretty on the original are quickly lost in this process; and too often cross-hatching would just turn to a blot.

(This and below are a couple of the covers for my Avalon sketchbooks.)

The other edge that working in fanzines at that time brought me was being able to network with people who would be my future competition and employers. At the age of 16 I was already introduced to most of the people that I would work for and with when I was ready to begin a career in comics 8 years later. I was corresponding with the likes of Joe Kubert and Stan Lee, Roy Thomas, Len Wein, Marv Wolfman, Alan Weiss, Al Milgrom, Jim Starlin and so many others whowere part of my fanzine circle, and those contacts would be invaluable later on.

And the competition! The professionals who drew the books were in their own unapproachable universe; at best I could strive to do my own poor imitations of their work. But with fanzines I was suddenly seeing what other amateur artists were doing and it was the spur I needed to start dramatically improving my own work. With the occasional homemade comic stories I was doing, I was laying out the pages with more care, using a lettering guide, and inking them with a pen and brush and even coloring them with ink washes. Both Ronn Foss and Grass Green were great mentors with helpful hints, passing on invaluable information to me; they would send me issues of their homemade comics to study. I was in heaven.

At the same time I was doing Masquerader I was also keeping a monthly "sketchbook" that I called Avalon (after the street that I lived on.) It was composed of story ideas, character designs. pinups and rough layouts of stories. I always had a part-time job during high school and got excellent grades; I really don't know where I found the time for all this. But then, I wasn't going out on a lot of dates. Apparently this schedule finally got to me in college when I became obsessed with playing basketball. Most of my drawing and fanzine work dropped dramatically in priority during this time. It was only after I was teaching school that I seriously sprained an ankle that kept me off the basketball court all summer; I rediscovered drawing and comics again, quit my teaching job and have never looked back. However, I still am obsessed with basketball.

|

| (That was then) |

|

| (This is now) |